- About

- Topics

- Story

- In-Depth

- Picks

- Opinion

- News

- Donate

- Signup for our newsletterOur Editors' Best Picks.Send

Read, Debate: Engage.

| topic: | Freedom of Expression |

|---|---|

| located: | Russia |

| editor: | Andrew Getto |

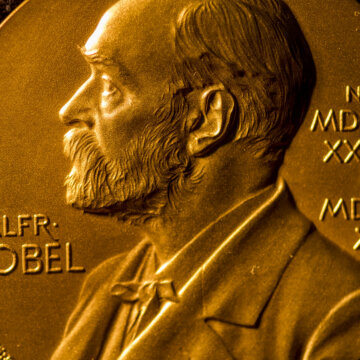

Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny - poisoned and imprisoned by the Putin regime - was considered one of the top picks for this year’s Nobel Peace Prize. Instead, the award went to a considerably less famous figure, Russian journalist Dmitry Muratov. Some people within the country are questioning the decision, but I believe it highlights an important fact: the price for doing real journalism in Russia is impossibly high.

Everyone knew that the inhabitants of the Kremlin were obscenely rich before Navalny revealed it, but his merit lies in tearing the blanket off. His blockbuster videos targeted dozens of top officials, including former president Dmitry Medvedev and the current lifetime ruler Vladimir Putin. Navalny also organised huge protests and tried to run for president himself. Then he survived poisoning by FSB agents, turned his own murder attempt into another investigation, and finally came back to Russia - to be immediately placed behind bars.

This is a powerful biography, worthy of any award there is; yet the prize went to an underdog. But this man’s mission is not only as important as Navalny’s, it has been just as dangerous.

In 1993, Muratov and his colleagues created Novaya Gazeta (The New Newspaper) and has mostly since been its editor-in-chief. The publication has focused on government wrongdoings and has taken swings at the most sensitive topics: from the war in Chechnya and terrorist attacks to the Laundromat schemes of moving money out of Russia.

As Muratov himself put it, “the award belongs to my deceased colleagues.” The newspaper’s uncompromising tone and the choice of topics has led to the deaths of many of the Novaya journalists. Here are just some of them.

In 2003, deputy editor Yuri Shchekochikhin died in a way reminiscent of Alexandr Litvinenko’s death: killed by the Kremlin with a radioactive substance. “Within two weeks, he turned into a profoundly old man, his hair was falling out in flocks, his skin stripped off his body almost completely,” his colleague recalls. The newspaper suspects that his investigations into senior officials of the FSB were to blame.

In 2006, legendary reporter Anna Politkovskaya, an outspoken critic of Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov, was shot dead in her apartment block. In 2009, a neo-Nazi shot dead young reporter Anastasia Baburova and Novaya’s lawyer Stanislav Markelov. That same year, human rights activist Natalya Estemirova was abducted in Chechnya and found dead in Ingushetia.

The newspaper claims that in almost every case, the official investigation has identified those who ordered the hits, but has covered them up.

In 1975, dissident Andrei Sakharov received the Nobel Peace Prize for daring to criticise the Kremlin and calling for disarmament in the middle of the Cold War.

In 1990, it went to the Soviet Union’s last liberal-leaning leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, who allowed the free discussion of sensitive topics. Thanks to that, Russian investigative journalism became at least possible.

But this year’s laureate proves that 30 years after the fall of the USSR, freedom of speech in Russia is not just a rare gem - it’s a blood diamond.

Image by: Alexander Mahmoud