- About

- Topics

- Story

- In-Depth

- Picks

- Opinion

- News

- Donate

- Signup for our newsletterOur Editors' Best Picks.Send

Read, Debate: Engage.

In the summer of 2000, I visited Port Harcourt, the capital of Rivers State in the Niger Delta and Africa’s undisputed oil hub, for the first time. I was spending my vacation with a relative, who at that time, was on the payroll of Shell Petroleum Development Corporation, the Nigerian subsidiary of the global giant.

My relative, Oluwaseyi, had recently returned from the Netherlands; having spent a year or so abroad on course posting ― a sort of professional advancement placement for local Shell staff in Nigeria. His beautiful apartment, painted in cheerful creamy colours, reeked of Dutch fragrances and the panoply of European collectibles from the trip filled a whole bedroom. In one part of the bedroom I stayed in, delicate ceramics jostled with an encyclopaedia of cook books for space. It was a farrago of finery. Yet Oluwaseyi lived in one of the gated compounds that dotted the periphery of Port Harcourt, sanitised communities for oil workers and commercial bankers, Nigeria’s small but emerging middle-class.

Without money or a stable salary, you couldn’t afford to live there at all. Occasionally, the entire household would venture out of the gated community for church, shopping or leisure. The East-West is a ring road that circumvents the bustling metropolis and caresses its many shanties as a mother would huddle her child.

One of our favourite destinations is the Shell RA, the grandest of the city’s gated communities. Shell’s residential area is a gilded cage for the corporation’s expatriates and domestic workforce. Manned by armed guards at all times, the RA offers European-style living conditions in the midst of squalor. Whitewashed chalets dot the landscape of the RA like Chinese lanterns in the night sky. The wide avenues were meticulously lined with stately trees and all kinds of ornamental shrubberies. The upscale residences were also fitted with the latest gadgetry and amenities. One would easily think one is in a picturesque Dutch town.

I loved the cool ambience of the RA. I would frequent the beauty salons at the recreational centre, listening to the endless chitchat of petroleum wives. It was a world away from another world ― one of pollution and poverty. The leafy neighbourhoods of the RA is a geographic landmark in the geo-history of Shell in Nigeria.

On the eve of the second world war in 1938, about a quarter of a century after Lord Fredrick Lugard amalgamated the colony of Lagos with the northern and southern protectorates into the modern state called Nigeria, Shell D‘Arcy was granted a concession to prospect for oil throughout the country. The company would strike the black gold 18 years later when petroleum was discovered in a remote village in the eastern Niger Delta.

Two Nigerian communities aptly represent rise and fall of Shell’s empire-building activities in the oil-rich Niger Delta. While Oloibiri is the spot where petroleum was discovered in commercial quantities, Ogoni is the land in which the corruption and collusion of the oil giant became known to the world.

Whereas Oloibiri is now located in present-day Bayelsa, after the state was carved out of the old Rivers State; Ogoni straddles a large area in Rivers State. Nonetheless, both communities bear the horrible scars of Shell’s entry into Nigerian territory.

Oloibiri: The Rise of Shell

Located in Ogbia local government area, one of the 774 subnational divisions of Nigeria, Oloibiri is a relic of the old glory of oil production in the Niger Delta. It was in this small community that oil prospectors from Shell first found petroleum in the whole of West Africa.

Writing in the Vanguard, Nigerian journalists Samuel Oyadongha and Emem Idio describe the current state of the settlement as ‘an abandoned fishing port after the anglers had left with their catch.’ True to the aphorism, Shell is one of the anglers that milked Oloibiri of its resources, leaving the community poorer than when they first arrived. The indigenes of Oloibiri are mostly Ijaws, a minority tribe in Nigeria’s multi-ethnic federation. They farmed their lands and fished from creeks and rivers. Oil palm is the predominant cash crop of the region. With the economic incursion of Shell, petroleum oil soon replaced oil palm as the major produce of Oloibiri ― to the profit of the company but the loss of the community.

Following the first shipment of oil in 1958, Shell began to expand its operations to other areas of the Niger Delta. A kind of Californian gold rush ensued as other key players joined the band wagon when exploration concessions were granted by the government to other foreign entities including Mobil and Elf.

Other major finds were made in the 60s but the early gains were stalled upon the start of the Nigerian Civil War in 1967. The conflict would last some three years. The 70s ushered in a new era: the oil boom. Data from the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) which Nigeria joined in 1971 revealed that the country traded almost $28 billion worth of petroleum products in 2006, exactly half a century after Shell debuted in Oloibiri. Yet the scale of want in the Niger Delta is unfathomable.

"Grinding poverty has robbed the indigenous people of the region of their dignity as farmlands were cleared and converted into oilfields."

Where hitherto rivers supplied aquatic bounty for fishermen, the creeks have been spoiled by massive oil spills.

Ogoni: The Fall of Shell

My first recollection of the word, Ogoni was in 1994 when my family would watch the news at nine. It was a family traditional to watch the network service of the Nigerian Television Authority. I also recall the word came with a number, 9. In time, I came to understand that the Ogoni Nine were Nigerian citizens that the regime of Abacha had arrested under false accusations of subverting the state. Their leader, Ken Saro-Wiwa, a Right Livelihood Award laureate, would be killed a year later on November 10, 1995.

Several months before that fateful execution, General Sani Abacha, the head of the military junta in charge of the country at that time had taken power for himself in a bloodless coup. Bent on securing his grip on power, Abacha saw Saro-Wiwa’s protest against the environmental degradation of his homeland, Ogoni, as an affront on his ‘quasi-presidential’ authority. Not wanting to lose control of his nascent ascent to the position of head of state, he swiftly had the dissenters tried in a military tribunal.

Shell has been repeatedly accused of colluding with the Nigerian government to deal with the Ogoni situation. Fingers have also been pointed at Shell for the role they played behind closed doors in the trial that sentenced Saro-Wiwa to death, by a legal process widely disparaged as a kangaroo court. It led to the expulsion of Nigeria from the Commonwealth. But the company has consistently denied these claims. Nonetheless, it is widely believed that the protesters were merely collateral damage in Shell’s petroleum operations in the Niger Delta.

“About 30 million people are living in the Niger Delta,” Nnimmo Bassey, another Right Livelihood awardee from Nigeria says in a fairplanet interview. “Ogoniland, which is only a part of the Niger Delta, is 1,000 square kilometers, with about 1 million inhabitants.” Bassey is currently with the Health of Mother Earth Foundation (HOMEF), a charitable organisation helped establish in Benin City, Nigeria. He says there is still a lot of ongoing pollution in the Niger Delta and part of his mission is to help in the promised clean-up of the area.

Nnimmo Bassey

Nnimmo Bassey

Nicholas Ibekwe, an investigative journalist with Premium Times corroborates Bassey’s statement. In 2017, he spent time in Ogoniland covering the legal battle between members of the community and Shell. His reportage was published as a dossier last May. Speaking of his time in Ogoni, Ibekwe says the people are very angry. He comments on why, “For such a place, the people are poor like most parts of Nigeria.

The degaradation of the land and the drinking water is one big problem. There were plenty of signposts with ‘Do Not Drink! Do Not Fish! Do Not Swim!’” Still not much progress has been made with the widely reported clean-up that the government says is underway.

Nubari Saatah, a native of the area lambastes the Buhari government for its duplicity on the problem. “Government keeps snapping photographs of the clean-up launch but nothing is happening,” Sataah complains.

British Justice or Brutish Justice

The influence of British law in the global system cannot be easily dismissed even after decades of decline following the collapse of the empire.

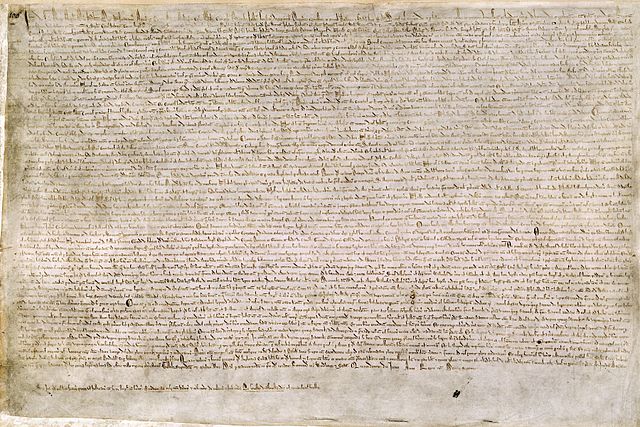

The legal system of the United Kingdom can be likened to a beautiful piece of ceramics that has been forged in a pre-medieval kiln, polished for many generations and showcased for use by one and all. Despite America’s economic and military, English customs still command international respect in many jurisdictions. For centuries, the Acts of Parliament decided the destiny of nations and peoples. Starting in 1215, six years after the founding of Cambridge University, the Magna Carta established the principle of the rule of law, for the first time.

The Great Charter essentially stripped royalty of their immense powers, stipulating that king and country were subject to the law. The Magna Carta was a revolutionary idea that predates the divine right of kings, a political-religious doctrine that was championed by James VI of Scotland in the 16th and 17th centuries and claims that monarchical authority is of God and thus, can be subject to human oversight. Although the Magna Carta originally contained 63 clauses, only 3 of those clauses remain extant in English law. One of the surviving three clauses reads: “No free man shall be seized or imprisoned, or stripped of his rights or possessions, or outlawed or exiled, or deprived of his standing in any other way, nor will we proceed with force against him, or send others to do so, except by the law of the land. To no one will we sell, to no one deny or delay right or justice.”

In the actions of British authorities against King Jaja of Opobo, the first sentenced of this clause was greatly abused. I first read about this royal person as a primary school student. His story was craft as a reading comprehension during English lessons but I would later realise that it transcends mastery of foreign language.

Jaja was a slave that rose to become a sovereign in his own right. He founded and exercised dominion over Opobo, a city-state in an area that is today known as Rivers State in southern Nigeria. His influence eventually put him at cross purposes with Britain imperialism in West Africa. He was thereafter arrested and exiled from his country. He died in 1891. In the actions of British authorities against the Ogoni people, the second sentence of above clause is now being abused. For too long, justice has been denied to the people of Ogoniland and today, the British judiciary is actively participating in that denial.

In February of 2018, a British court dismissed an appeal in the case that the Shell Petroleum Development Company should be tried for oil spills in the United Kingdom rather than in Nigeria where the spillages occurred. Shell has always insisted that most of the spills were cause by saboteurs. Yet Amnesty International claims its researchers have found at least 89 spills which might have been deliberately mislabelled as theft or sabotage. The rights group indicated that of the 89 spills, 46 are from Shell and the remainder are from Eni, the Italian oil giant, currently facing similar prosecution in Milan.

But the shamelessness of the denial of justice pales in contrast to the delay of the Ogoni clean-up project which experts say could take as long as 30 years, almost 8 presidential terms under Nigeria’s current constitution. Despite the delay associated with the clean-up, Nnimmo Bassey of Health of the Earth Foundation (HOMEF) is optimistic about the joint endeavour to restore the Niger Delta to its pristine state. He spoke with fairplanet.

fairplanet: Do you think security might pose a challenge to the Ogoni clean-up project as there have been concerns in recent years about militant local groups blackmailing the government and taking foreigners, especially workers of the oil companies, as hostages?

Nnimmo Bassey: I think with regard to the clean-up, everybody has an agreement, everybody is involved and everybody is anxious for the cleaning to start. Therefore, I don’t see a security problem with regard to the clean-up. There might be some security issues with the government around in the country, but there is nothing really that could stop the clean-up. None. You know, the clean-up has a lot of implications for everybody. There are quite a lot of young people from Ogoni that are currently running a second stage of training to be part of the clean-up. That is very important. The clean-up won't commence with a workforce coming from elsewhere. That would cause some instability, to put it nicely. In the Shell clean-up that has already started, about ninety percent of the workforce come from Ogoni. This is something that could develop very positively in the long run.

Is it correct that the Ogoni project is a sort of compensatory action by the Nigerian government and the oil companies for the genocide that was committed on the Ogoni people in 1996?

That’s a difficult question. Let's put it that way: The clean-up is a response to the undeniable fact of evidence-based output of the research carried out by UNEP in the region, showing that the environment is absolutely polluted and the drilling caused that horrific situation. And the clean-up will put on hold that deteriorating situation, which is a big shame for the country and a big threat to the people in Niger-Delta.

Your organization is cooperating with the German-based NGO, One Earth One Ocean. What does that cooperation look like?

One Earth One Ocean is an NGO that provides assistance to the clean-up, and they don’t ask for payment or contracts from the government, rather they’re providing training for the local people, and technology that is good for the environment. I’ve seen a demonstration of it in one of our community training programmes. And everyone believes that, with organisations that bring assistance to the communities and to the people of Nigeria, they should be most welcome. They bring not-for-profit help that is very innovative, and that is something that you rarely see in that part of the world.

Is the Nigerian government satisfied with the fact that foreign NGOs are part of the project? Or would they prefer to have domestic companies doing the job, since there’s so much money involved in a project that could last 30 years or more?

I can’t speak for the government. But I can say Nigerians are happy with help from NGOs. They showed that they are interested in the environment and the people, so they are most welcome; they showed solidarity with the people and the culture, and our people are grateful for that. People are very open here, and as far as I can say the government is not antagonistic to organisations that come to help.