- About

- Topics

- Story

- In-Depth

- Picks

- Opinion

- News

- Donate

- Signup for our newsletterOur Editors' Best Picks.Send

Read, Debate: Engage.

The Galápagos Islands, an archipelago off the western coast of Ecuador, remains a unique wildlife sanctuary almost 200 years after Charles Darwin found there the inspiration and knowledge for On the Origin of Species, a book that revolutionised the way we think about nature.

Amid tourists from all over the world who cross the oceans to meet giant turtles and dive in the Galápagos Islands’ rich waters, however, lurks a hidden threat to the environment: giant Chinese fishing fleets that have been visiting the international waters just outside Ecuador’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ) around the islands every year since 2017, and are accused of illegal fishing and plundering fishing stocks, including endangered species.

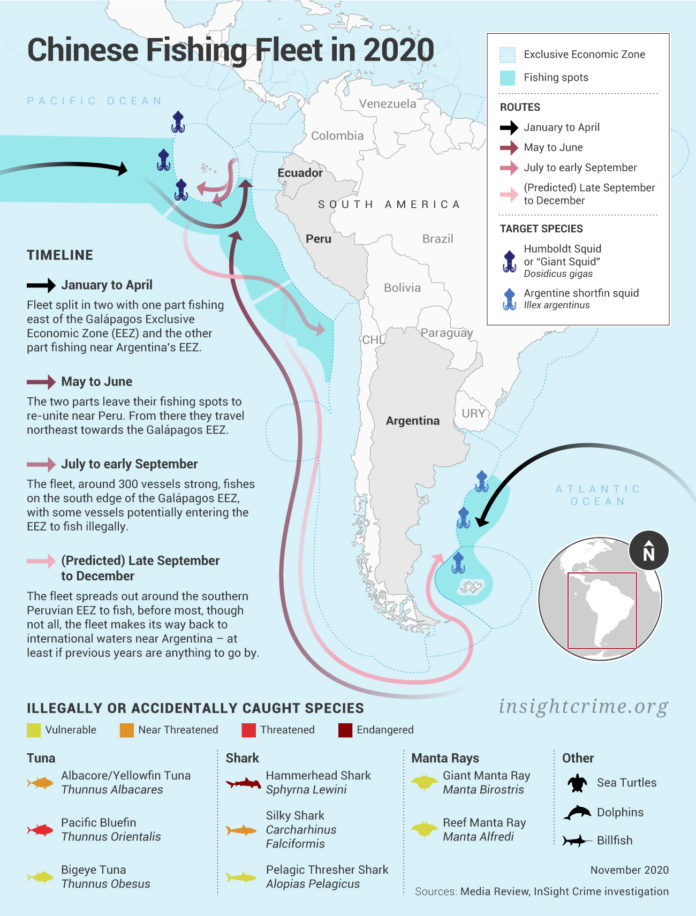

Between July and September 2020, more than 300 Chinese fishing vessels swarmed the highly biodiverse waters near the Galápagos Islands, just around the edge of the EEZ. Mostly made up of mass trawlers, which are banned in Chinese waters, the fleet used overhead lights and industrial jigging machines to attract and catch vast quantities of squid and fish. But the sheer size of the Chinese fleet prompted an international outcry and widespread concerns among conservationists who fear that it would not only overfish the squid and catch endangered species such as sharks and rays, but also enter the EEZ and illegally fish there.

At the time, China's ambassador to Ecuador said that China has a zero tolerance policy toward illegal fishing and their fleet followed international fishing regulations. In response, the Ecuadorian authorities said that while the fleet did not enter the country’s water, nearly half of them had turned off their GPS-based tracking and identification systems for certain periods of time, which raised suspicions of a strategy known as "going dark at sea," which is often used during illegal fishing. A report published by HawkEye 360, a US-based analytics company, also showed that unidentified vessels were present inside Ecuador’s EEZ during the same time as many Chinese-owned fishing vessels were undetectable.

Sources: Media Review, InSight Crime investigation

Under a United Nations maritime treaty, to which China is a signatory, industrial fishing vessels are obliged to continuously transmit what’s known as an automated identification system, or AIS, to avoid collisions. There can be legitimate reasons for a break, like avoiding pirates or poor satellite coverage. But another report by the conservation NGO Oceana shows that these vessels switched off their signals on average for two days at a time, with the longest break being around 17 days.

Environmental concerns regarding China have been particularly high in Ecuador since 2017, when the Chinese-owned ship Fu Yuan Yu Leng 999 was intercepted inside the Galápagos Marine Reserve with 300 tons of sharks onboard, many of which were later identified to be vulnerable or endangered species that inhabit the waters surrounding Galápagos. Another similar case was a shipment of 26 tons of shark fins (harnessed from 38,500 sharks) from Ecuador which was seized upon arriving in Hong Kong in May 2020.

Illegal, unregulated and unreported fishing (IUU) makes up the sixth most profitable global criminal economy, with estimated revenues of 15 to 36 billion USD, states a 2017 report by Global Financial Integrity. With a fishing fleet of almost 17,000 vessels, China is not only the world’s largest seafood exporter, but in 2019, it also ranked the lowest-performing country on illegal fishing around the world. In addition, Interpol and various rights organisations have long highlighted that there is a strong link between IUU fishing and other organised crimes.

"Even in Ecuador, there was a recent news story about the seizure of a shipment where apart from finding shark fins, they also found drugs," said Mauricio Castrejón, a marine biologist and Galápagos fisheries manager for Conservation International. He added that illegal fishing is often a sign for other underlying criminal activities such as drug and arms trafficking, money laundering and even human rights abuses, including modern slavery.

According to a 2021 Greenpeace report, China, Taiwan, Japan, Russia, Spain, South Korea and Thailand have the highest risk of modern slavery in their fishing industries. The most typical example of this is the employment of migrant fishers, who make up most of the crew and often come from Southeast Asia. They are kept at sea for extended periods, sometimes years, and frequently have their salaries reduced, or even withheld; with nowhere to escape, they are reportedly subjected to forced labour and harsh working conditions. In extreme cases, this results in serious injuries, physical abuses and even death.

The international backlash over China’s distant water fishing fleet has managed to push for some reform. In 2020, China introduced stricter penalties on fishing companies that are found to be breaching regulations, such as manipulating their transceivers. They’ve also banned blacklisted vessels from entering Chinese ports, increased reporting requirements for transshipments on international waters, and implemented off-season moratoriums on squid fishing in international waters near Ecuador and Argentina.

There are also growing calls to end harmful fishing subsidies that promote overfishing and indirectly contribute to IUU fishing as well. "If all the harmful subsidies would be eliminated by 2050, which is very ambitious, there would be a 12.5 percent increase in global fish mass, meaning about 35 million more tonnes of fish in the water," said Ernesto Fernández Monge, an international commercial law specialist at The Pew Charitable Trusts.

Global fishing subsidies are estimated at 35.4 billion USD, according to a 2019 study published in Marine Policy. The top five subsidisers are China, the EU, the United States, South Korea and Japan. Not all subsidies are considered "harmful", but "subsidies to distant-water fishing fleets must be eliminated to prevent overfishing on the high seas and in waters under national jurisdiction. Such subsidies threaten low-income countries that rely on fish for food sovereignty," according to an open letter published by nearly 300 scientists in Science Magazine, in which they call on the members of the World Trade Organization to reach an agreement regarding the ban of harmful fishing subsidies.

Meanwhile, the Ecuadorian government also faces its fair share of criticism on how it has been handling not only the giant Chinese fleet but IUU fishing activities by neighbouring countries and its own domestic fleet.

The European Union, the biggest buyer of Ecuadorian tuna, hit Ecuador with a so-called "yellow card" in 2019 and has urged the country to step up its actions in the fight against IUU fishing or risk losing access to its market. Fishing companies in Ecuador employ 100,000 people, and contribute $1.6 billion a year, 1.5 percent of the GDP, to the economy. The European Commission has also identified limitations in the fisheries’ legal framework.

A good example of this is the loophole of Ecuador’s Decree 486, signed by then-President Rafael Correa in 2007, which prohibits the catching of sharks. There is only one exception: if the shark is caught "incidentally", meaning caught by accident in nets or on hooks destined to catch other species. Sharks in this bycatch must be sold in their entirety and only by those who obtained a permit by the Ecuadorian Ministry of Environment.

However, conservationists agree that this loophole of the degree is often taken advantage of, and under the guise of bycatch, thousands of sharks are caught and exported to the global market.

According to Castrejón, the number of sharks legally sold from bycatch is not significantly different from the amount that was caught before the introduction of Decree 486, despite market prices somewhat dropping. Only the number of species reportedly caught has decreased from 28 to 13 species. "This is because there has been overexploitation of these species, not just illegally in Ecuador, but also in neighbouring countries, leading to local extinction of these species," said Castrejón of Conservation International. "That’s why they are no longer reported in the catch because there is obviously a decrease of biodiversity, which reflects in the composition of the catch."

There is no fishing method that doesn’t include bycatch, claims Castrejón, and so there should be complementary regulations to increase the efficiency of Decree 486 and minimise the incidents when purposeful fishing of sharks is reported as 'incidental'. "There should be an adequate number of observers onboard or an electronic monitoring system," he said, "They should also create permanent or temporary no-catch zones because it’s much easier to monitor whether a fishing vessel enters such zones than to determine which part of its catch was truly 'incidental’."

That said, the Ecuadorian government has made some encouraging reforms to crack down on illegal fishing and bolster ocean governance. The South American nation joined in December 2020 the Global Fishing Watch platform, facilitating enhanced monitoring of the 1,200 vessels that make up Ecuador’s industrial and small-scale fishing fleets. In April 2020, the Ecuadorian national assembly passed a law that increases fines for illegal fishers up to $700,000. Ships are now banned from selling three endangered species of shark, even if they are bycatch.

However, the law is yet to be fully implemented as some regulations, such as defying the limit of bycatch, are yet to be finalised, which is raising concerns among conservationists.

The Galápagos Islands are a key stop on a larger transnational illegal fishing route that includes Argentina, Chile and Peru. Thus, scientists and conservation NGOs believe strengthening regional cooperation, especially to monitor fishing activities on the high seas - waters beyond national jurisdiction - off the coast of South America would be a more efficient way to combat illegal fishing.

According to WWF Ecuador, placing more observers on fishing vessels, especially on foreign ones, banning transshipments at high seas (when fishing ships unload their catch on a cargo ship instead of returning to their home ports), and cross-checking fishing licenses of foreign fishing vessels with regional authorities could be some concrete measures to tackle the IUU fishing.

Meanwhile, there are also growing calls to include more restrictions on fishing as part of negotiations currently underway on the first-ever High Seas Treaty, brought forward by the UN. The aim is to reach an agreement on the treaty by early 2022, and it could result in an international, legally binding deal that would establish marine protected areas on the high seas.