- About

- Topics

- Picks

- Audio

- Story

- In-Depth

- Opinion

- News

- Donate

-

Signup for our newsletterOur Editors' Best Picks.Send

Read, Debate: Engage.

| June 19, 2022 | |

|---|---|

| topic: | Migration |

| tags: | #migrants, #Africa, #Brazil |

| located: | Brazil |

| by: | Ellen Nemitz |

Rosy Ngalula Kamayi was born in Congo. In 2018, she chose Brazil as her new home, pursuing a better life where her cousins were already living. She does not regret her decision. "Brazil is a country with many opportunities for those who know how to take advantage of them," she told FairPlanet.

Indeed, Kamayi goes after her dreams: she applied for a competitive public university in Curitiba, a city in southern Brazil, and is now enrolled in a law program. To that, she had to face considerable prejudice and discouraging sentiments by people who did not believe in her ability to achieve her goals.

Kamayi is also responsible for the communication of the Bomoko Association of African Migrants in Curitiba, founded in March 2020 - just prior to the covid-19 pandemic spreading across Brazil. In Lingala language, she explained, the word Bomoko means 'unity'. "We noticed that there are several immigrants from Africa here in Brazil who don't know [other African immigrants]. Sometimes they are alone, going through a situation and needing help, but they don't know anyone and don't know where to look for it," she said.

Bomoko provides support to the community - with food or clothes, for instance - but is also a safe space that gives people a sense of belonging. "Sometimes other communities, such as Venezuelans, come to ask for help, and we help them, too," she added.

Kamayi does not let fear or despair make her give up her dreams. Following the brutal murder of Moïse Mugenyi Kabagambe - a 24 year-old Congolese migrant beaten to death for requesting delayed payments for his work at a beach bar in Rio de Janeiro - on 24 January, 2022, she joined protesters in demanding justice. And while tragic event did not undermine Kamayi's view of Brazilians as a non-violent people, for Miguel Pachioni, a communications advisor at the press office of UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees) in Brazil, the incident "demonstrates that we are not a welcoming society as one might imagine." He regards this notion as "a true social myth."

Kamayi recognises the lack of support by the local government for African migrants Brazil, particularly when it comes to access to education and the labour market. Pachioni of UNHCR confirmed that only Venezuelans are eligible to participate in a migrant assimilation program - the Operação Acolhida. "There are no programs or actions by UNHCR and our partners specifically delimited to nationalities or other possible cohort profiles, such as religion, political opinion, etc."

Referring to reports stating that some African migrants intend to leave Brazil due to safety concerns in the aftermath of Kabagambe's murder, Pachioni argued that this single event did not, as far as he could tell, precipitate a massive exodus.

Although Brazilians' treatment of African migrants is not always overtly violent, Pachioni recognises that systemic racism and symbolic violence emenating from ethnic and racial prejudice, xenophobia and machismo are manifested in certain cenarios, specially when it comes to finding a job.

According to a report titled "2011-2020: a decade of challenges for immigration and refuge in Brazil," organised by the Observatory of International Migration (OBMigra), nearly 9 thousand people from Africa currently partake in Brazil's formal labour market, representing 5.2 percent of the migrant workforce. Their average monthly income in 2020 was 2,698 Brazilian Real (approximately $530 at current the exchange rate), which is nearly half of the average of all migrants.

Despite the grueling conditions in which many migrants live, Brazil can be a safe port for those seeking a new home. According to Pachioni, there are at least three reasons why Africans seek asylum in Brazil: the 2017 Migration Law, which grants migrants access to documentation such as ID and an employment card; the educational, work and income opportunities - especially before the pandemic, when Brazil had registered a promising economic development (the country's southern and southeastern regions attract the largest number of African migrants due to their economic potential, according to Pachioni); and social and familial ties with people already living in Brazil.

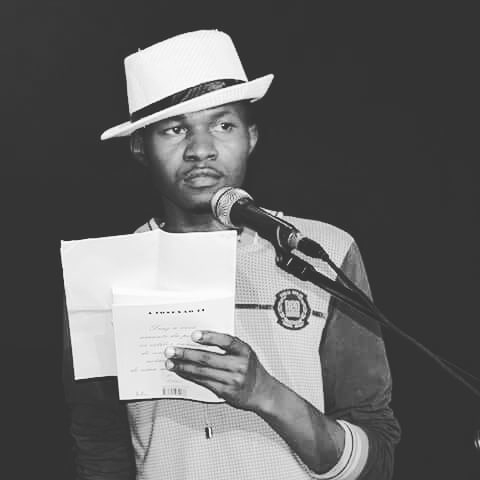

More than 35,000 African migrants currently live in Brazil, according to the Federal Police. One of them is Moisés António, who was born in a province near Luanda, Angola, where he graduated and worked as an English teacher for Brazilians.

The inability to publish his book of poems back home, combined with a range of and a strong urge to discover the world, compelled António to leave Angola. "Brazil was the country that attracted my attention most, [partly due to] my familiarity with Brazilians."

Staying at an acquaintance house as a favour in 2016, António faced prejudice and racial slurs. Living in the streets and starving was a constant fear for António, since he did not have a job at that time.

"On the other hand, I had generous people who helped me. A friend of mine offered me an online job to translate an English language course, which helped me to rent a room in Curitiba," he told FairPlanet.

António eventually got a regular job as an English teacher at a language school, where he needed to overcome the prejudice regarding his experience and professional capacity. "Nobody could bring me down. I showed my wisdom, my intelligence, my talent and that captivated people a lot. I proved that I knew things that even Brazilians didn't know."

Art is a tool António always used to express his feelings, thoughts, experiences and memories. "I always liked to read, and poetry was a way I used to vent," said the author of five published books. "I expressed my anxieties, revolts, protests, problems that plague the country to this day and also things related to romanticism, disappointments... many things mixed up!"

His poetry gained widespread public attention during the celebrations of Africa Day, held in Curitiba in May 2022 by the Bomoko Association, and also from the cultural scene in Brazil. Following a request to write about the experience of being a migrant, António wrote the poem Eu sou migrante in Portuguese - which was later used in textbooks in national schools.

António translated the poem into English especially for FairPlanet. Now titled "I am an immigrant," the poem represents our shared hopes of a world without borders, without prejudice and with equal opportunities for all.

The poem was inspired by the various hardships faced by migrants which António observed, such as the struggle to find work, even for migrants holding university degrees, or being turned away at borders.

"I sought poetry as a weapon of protest, not only about migration, but about injustices, racism, against wars all over the world," António said. "My poetry is based on facts."

I AM AN IMMIGRANT

By Moisés António

I am an immigrant from far beyond overseas

There, from the other side of the ocean

Forced to leave the country

Yes, the country of my origin

In which for life,

I had been fighting for centuries

Knocking on never unopened doors

Which were always closed

I have no land

There, where I come from

which you call or say to be my land...

I was like an arrow

Eager to go forward

But had been consistently pulled backward

Harder and harder!

And, by pulling me so much

I was hurled vehemently

to hit the target

And came to end up here!

I am an immigrant

I have no land

Everywhere is a land

It doesn’t matter if here or there!

I wish there were no borders!

I wish there were no laws

Laws that tie, separate,

Harass, injure and shake us!

Oh if there were no borders

Geographic divisions

And all the men were only men,

With no distinction of races, colors, or nationalities!

Why am I to blame for being Black or White?

A Christian or Muslim? A Hindu or Buddhist?

A Jew or Samaritan?

If maybe there were no Black or White races!

In fact, there are not

The only race that exists is...

The human race!

I am an immigrant, emigrant, migrant

Tough with the strength to live, eager to live

I’m resistible like an African Lion

I have the power of the wild Hawk’s claws

I’m persistent like the moving sea waves

So, all I beg is to be respected

I just want to live life…

Because the Earth is ours... for all of us

Created by God, and given to all human beings

It doesn’t matter where, if here or there!

Image by Kaspars Eglitis.

By copying the embed code below, you agree to adhere to our republishing guidelines.