- About

- Topics

- Picks

- Audio

- Story

- In-Depth

- Opinion

- News

- Donate

-

Signup for our newsletterOur Editors' Best Picks.Send

Read, Debate: Engage.

| April 08, 2019 | |

|---|---|

| topic: | Peace and Reconciliation |

| tags: | #Peru, #indigenous, #Jesús Cossio, #mining, #human rights, #discrimination |

| located: | Peru |

| by: | Pablo Pérez Álvarez |

In all of them, he has portrayed the situation of the indigenous population, trapped between the army and the revolutionary organisation Shining Path, in the first case, and between the mining international corporations’ interest and their lifestyle and their environment, in the latter one.

FairPlanet: When and why did you start making comic books about the Peruvian internal conflict?

Jesús Cossio: I made the first one, entitled ‘Rupay’ (an indigenous word meaning “burning” or “childbirth”), together with two friends when the Truth and Reconciliation Commission published its report, in 2003. In spite of being a very important document and a very uncommon - especially for Latin American standards- recount of the human right abuses (executed by the State, Shining Path and the Tupac Amaru Revolutionary Movement during the 1980s and 1990s) and the fact that is should have been debated or taught, it has been attacked since his release.

As in other countries, there are ultra-conservative sectors of society that, they are not only against the discussion of certain information, but they directly deny that information and say it never happened. They are denier or revisionist groups. When we saw this, we wondered what could we do to endorse the idea that the human rights violations must be discussed at pedagogical, citizen and social levels. We decided to make a comic to help spread that information in a non-conventional way. Later, I made ‘Barbarie’ (‘Barbarism’.) Both of them tell emblematic cases of violence that my generation and other two generations have heard about but didn’t really know what happened. I call them documentary comics.

What’s the reason of this unawareness about an issue historically so recent?

It’s an issue not only taboo but also criminalised. There are in Peru nowadays the stigmatisation of any subject related to Shining Path. Teachers cannot talk about it in the schools because they fear being accused of being apologists for it. Even artists and documentary makers are afraid of getting their professional careers curtailed. But on the other hand, we are seeing the release of many documentaries, books, surveys,… trying to delve into Shining Path without censure. Sometimes the context is so conservative that the fact these projects exist is shocking. I’m not talking here about my comics, as they are below the radar, but about books, interviews to former Shining Path members and lectures about women inside Shining Path. There is a very recalcitrant sector in the public opinion that has made this obscure knowledge.

Have you addressed the internal conflict issue in some other work?

I have a work entitled ‘The years of terror. 50 questions about the internal conflict’, but it’s not a comic, but an illustrated book. I made it for the schools or for the parents who want to introduce their children in the matter. They are 50 basic questions with short answers and illustrations supporting them. It was published in 2016. It’s acquired by parents or teachers who want to show them to their students and they found it very useful because reading is becoming increasingly hard for teenagers.

And then I have ‘Retratos’ a series named portraits drawn from talked memories of the relatives of the victims of Accomarca (an Andean village where 60 indigenous peasants, including 30 children, were tortured, raped, killed and burned by the army in 1985). I have done it with a photographer who took pictures of 25 people who didn’t have any pictures from their disappeared relatives as I talked with them. After that, I made extrapolations of their faces and some kind of symbolic portraits. The objective is to replicate this project with other villages with disappeared people form whom there are not any picture, any visual remain.

Do you think that you make affordable this kind of issues to a certain public that can’t be reached with another means?

I think that happens. In fact, ‘Rupay’ is required for first-year students in some university. They say that youths nowadays face difficulties in reading so they use it to involve the students in the subject of political violence in Peru, that is not very often addressed. But I also think that some documentaries recently released, some of them even in the cinemas, are more effective. These audiovisual and graphic works provide a higher relevance to this issue than some years ago. There are even fiction films. A youngster probably wouldn’t go to watch a documentary on the Truth Commission, but he or she will watch a thriller where one of the characters is a former soldier who has perpetrated human right abuses. Young people are more openminded than some media and some politicians think. They are treated as idiots who would become terrorists if they are exposed to some information.

Have you made more documentary comics beyond the internal conflict issue?

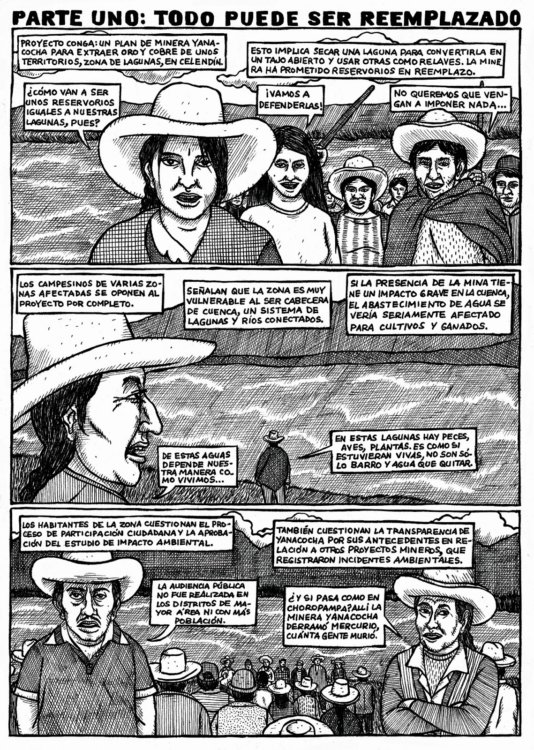

I made a comic book on Conga (a gold mining project in the Andes mountains strongly opposed by quecua-speaking peasants because it would contaminate the local lagoons) and a web-comic on another environmental dispute on a mine for an independent group of journalists, Ojo Público (Public Eye). They asked me to make an interactive web-comic and it was published two years ago. Last year we published the printed edition. I think it was the first time that something similar it’s been made in Latin America.

What is this comic web about?

It’s about the probably most controversial mining project at present in Peru, the gold mine of Tía María, in Arequipa. It’s a very important investment at it’s in limbo. There’s a big confrontation between the stance of the capital, Lima, where the project is imperative, and the one of Arequipa, where the rural population is discussing the value of the agricultural labour, the farming land and Heritage of the rural labour and the environmental dangers of a mining investment without the proper care and uncontrolled. The resistance is so strong that so far five persons have died in the protests.

All your works seem to have as a backdrop the common factor of the discrimination of the indigenous population from the Andes and the lack of understanding between them and the mestizo and white population from the coast.

That’s right and precisely the Truth Commission report says that one of the key causes of the violence was the discrimination and the racism of the rural zones population. That’s still been debated today in the Peruvian society. I could see it very clearly when we made the web-comic about the Tia Maria project because we had to check what the media in Lima said about it and then travel to the zone. If you are led only by what Lima’s newspapers you may think that people in Tía María are just ignorant backward peasants, and in addition to this they are manipulated by leftist environmental groups and potential terrorists.

But when you go there you realise that they are very informed people, not manipulated at all and with very broad knowledge. In Peru, as in other Latin American countries, Afro-descendant and indigenous population are being historically discriminated and I try to work for that to end. And I think many people are trying to do so in theatre pieces, movies…

What’s the potential of the comic as a communication tool to take this kind of issues to people?

The image can always cut the apparently rational connection that you have with the text. There’s a moment when your brain stops thinking and tries to empathise in a non-rational way. That kind of understanding something without trying to rationalise it is what the drawing of the visual image in general gives you. The comic can get this other kind of connection. Another advantage is that you can recreate events with just a pencil and a paper. You don’t need 200 actors and a stagging, that would be very expensive.

Nineteen years after the end of the internal conflict, how has Peru evolved and healed the wounds that it opened?

First, although the conflict officially ended, there is still a remaining Shining Path in the Peruvian jungle, associated with drug dealers. Besides, we have now organised crime groups and illegal mining. The illegal miners are replicating some of the brutalities of Shining Path, like the slavery and the sexual exploitation of women, even at some levels never seen before with Shining Path. They build lawless territories where those who raise their voices are killed. On the other hand, there’s a lot of work to do to overcome the fear to discuss openly about the conflict, its causes and why so many people opted for the armed fighting, maybe with legitimate motivations but committing crimes and murders precisely against the people they should have been protecting.

By copying the embed code below, you agree to adhere to our republishing guidelines.