- About

- Topics

- Picks

- Audio

- Story

- In-Depth

- Opinion

- News

- Donate

-

Signup for our newsletterOur Editors' Best Picks.Send

Read, Debate: Engage.

| August 20, 2015 | |

|---|---|

| topic: | Air Pollution |

| tags: | #Capoacán, #Coatzacoalcos, #coke plant, #contamination, #fuel, #Greenpeace, #Jaltipan, #Mexico, #oil company, #oil residue, #Pemex, #pet coke, #prisoner, #Red Cross, #Tatexto |

| located: | Mexico |

| by: | Pablo Pérez Álvarez |

Elena Riquer passes the palm of her hand over the window frame of her home, in the Mexican village of Capoacán, on the banks of the abundant river Coatzacoalcos, and then shows it. It’s completely black. Whenever they are cleaned, in a few days they are black again. And not only over the windows. The walls, the roof, the surface of the water in the wells used to do laundry or even for drinking… Everything gets covered by a coat of inky dust.

It’s formed by the particles released by the pet coke processing plant located just on the opposite bank of the river, 200 meters away, part of the Lázaro Cárdenas refinery, located in the Veracruz state (East Mexico). The pet coke is an oil residue that, once processed, is used as fuel in big industrial plants.

Just when night falls, the coke plant begins working at full capacity. The glare from his chimneys lights the night several miles around and the noise it creates, an incessant combustion murmur, is clearly perceptible in Capoacán, a humble fishing village with 2,000 inhabitants. From time to time, when the high flues vent, the murmur becomes a roar that disturbs the neighbour’s sleep.

But the noise isn’t the worst. Neither is the black dust. Nor even the unbearable heat the plant generates intensifying the usually high temperatures in this jungle-covered region.

The worst is the sickening stink coming from the other side of the Coatzacoalcos (which soaks even the food) and the constant health problems suffered by neighbours, who blame the coke plant for it: headaches, respiratory difficulties, skin rashes… And other more serious illnesses which are not registered because authorities don’t make any medical studies to know the health impacts of the coke plant on the residents.

“I feel that even my face aches. We cannot stand the headaches,” Elena Riquer complains. This 57-years-old neighbour explains that after the pet coke plant began operating, five years ago, she went to the Red Cross for some clinic analysis because the smoke used to suffocate her. “They told me I have chronic bronchitis.”

Rocío Sánchez, her daughter-in-law, got pregnant four years ago and tells that during the pregnancy she used to have constant aches and doctors told her there was an abortion risk. From birth, her daughter has suffered itching: “She even pulls out her hair when scratching”.

“Sometimes we are in the porch trying to refresh ourselves and suddenly that smell appears. The babies, if they are eating, even vomit. It’s very penetrating,” she explains.

Another neighbour, Juan Luis Francisco, is worried about the impact of smoke from the refinery, especially on the children. “We go out of the village for work, but they are here all day long”.

In the hot season, he claims, they cannot have their windows open. “It’s better to bear the heat than to smell that strong smell. When the wind changes direction and brings the stink to us, children must get inside the house. We are virtually prisoners in our own home.”

Lorenzo Bozada, a biologist who has been investigating the concentrations of mercury in the water and fish of this region and its effects on health for several years, says that according to Mexican legislation “there shouldn’t be human settlements closer than one kilometre from the refinery”.

“The problem is that when this one began there was nothing in the surroundings. Then the employees established homes close to the refinery because the working days included a midday break, so they were able to go home for lunch. This way, the refinery is now surrounded by human settlements,” he says. This, he adds, happens in all the Mexican oil complexes.

The investigator, son and grandson of oil workers, calls into question the results of an atmospheric sampling ordered by Pemex (the state-owned Mexican oil company which owns the refinery): “They indicate that the air here is the cleanest in all of Mexico. That’s impossible”.

For him, “that data is not credible” because some years ago, before the pet coke began to be processed, an ecological local organization, the Tatexto Ecologic Producer’s Association (Apetac, in Spanish), made a sampling and found high concentrations of substances like benzene, toluene and sulphur.

Gonzalo Rodríguez, from Apetac, points out that they were “very rudimentary samplings (with buckets) but they proved the high concentration of polluting substances” at levels of up to 200 particles per million.

In addition to this, Bozada says “it’s proved that pet coke has a high quantity of sulphur, heavy metals like nickel or cobalt, and aromatic hydrocarbons”.

The scientist emphasizes that Mexican law is very permissive with the emission of pollutants to the atmosphere, but if one compares the sampling results with the indicators of neighbouring country the United States, the emissions are way over the recommended levels for public health: “We are at the same level of emissions of Senegal."

Besides that, Bozada fears that pet coke smoke carries mercury, something that, he admits, hasn’t yet been proved scientifically.

But what has been proved is that fish founded in the part of Coatzacoalcos river where the refinery pours its residues have high concentrations of this element highly harmful for health.

“This river is already very polluted. Soon it’s going to be a dead river,” Rodríguez warns.

Rafael Riquer, the 56-year-old brother of Elena, can no longer earn his living as he always did, as a fisherman: “If you go now to fish at the river, you don’t get anything. Since the pet coke plant is there the fishing has worsened. So nowadays we don’t go to fish, we go to Pemex to ask for temporary work.”

Gonzalo Rodríguez assesses that cases of cancer have increased in the region, but local health authorities are not concerned about it: “They haven’t even reported how many people die every year from cancer or from kidney diseases”.

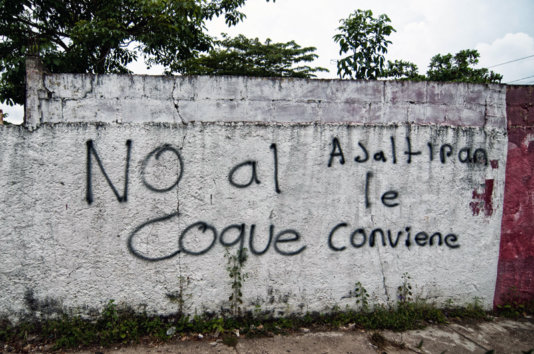

Capoacán and other villages close to the Lázaro Cárdenas refinery are not the only victims of pet coke in this area. In Jaltipan, only 20 kilometres away, an open air storage facility for pet coke was opened two years ago. This solid fuel is taken by train to this place and piled up in pits before being sent to other places in the country to fuel industrial plants.

This has divided the neighbours into those who support the store and those who see in it a source of contamination and demand its closure.

“Pet coke has the heaviest chemical elements, like chrome, vanadium, nickel and lead, and a high level of sulphur. It’s also been scientifically proven that they can cause cancer,” argues José Luis Jerónimo, a biochemical engineer against the plant.

The company, he explains, “has placed geomembranes (in the pits where coke is stored), made mainly by cellulose, to make sure that when it’s too rainy, all the water loaded with those heavy chemical elements get to the water tables”, but “that’s not enough because that kind of ground is very acidic and, when raining, used to be very soft. So when it gets dry it cracks and the water finds its way down”.

Greenpeace has expressed its concerns about the possible aquifers contamination because of the coke and has warned that this is catalogued as a dangerous residue by the Mexican government and so cannot be stored in open air, even less in bodies of water or their surroundings.

Some Jaltipan neighbours are also worried because of the pollution that, they say, is spread by air. Although the company moistenes the coke hills with nebulised water, the heavy heat in the region evaporates it quickly.

Julisa Hernández, one of the most active objectors to the coke store, says that “the crops in the region are completely damaged by it. The farmers claim that even the fertilizers are useless to revitalize their lands, and they don’t produce anymore. The ground is suffering desertification."

Besides, she adds, “every time it rains there are some deaths among the cattle”. After pet coke began arriving, they counted a dozen dead that they attribute to water contamination. “River water passes first by the coke storage facility and then to the cattle parcels, irrigating the pasture, where it is then eaten by the animals.”

Hernández also blames pet coke for the increase of in fish mortality and the butterflies’ disappearance. “You can hardly see then around. It seems that somebody used a chemical weapon”, she complains.

By copying the embed code below, you agree to adhere to our republishing guidelines.