- About

- Topics

- Picks

- Audio

- Story

- In-Depth

- Opinion

- News

- Donate

-

Signup for our newsletterOur Editors' Best Picks.Send

Read, Debate: Engage.

| July 19, 2023 | |

|---|---|

| topic: | Refugees and Asylum |

| tags: | #India, #Rohingya, #refugees, #education, #language |

| located: | India, Myanmar |

| by: | Asma Hafiz |

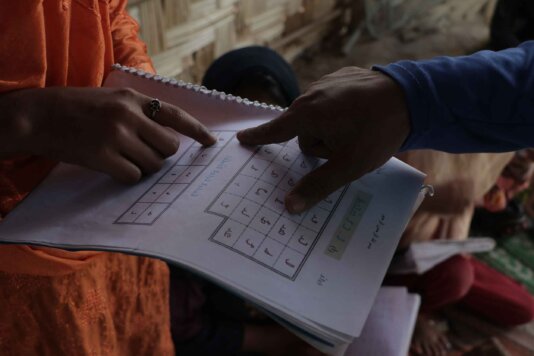

A group of 15 children bundled together in a small shanty made of bamboo and plastic and read out from their notebooks in a Rohingya refugee camp in the Faridabad district of Haryana, 28 kilometres away from the Indian capital New Delhi.

Their teacher, Mohammad Ismail, instructed them to repeat the Rohingya alphabet after him. He teaches them Arabic, Urdu and Rohingya. With no hope of returning to his homeland, Ismail took upon himself the task of teaching these children their native language.

Escaping persecution in Myanmar, thousands of Rohingya refugees sought safety and refuge in neighbouring countries such as Malaysia, Indonesia, India, Thailand and Bangladesh.

India currently shelters an estimated population of 40,000 Rohingya refugees. Human Rights Watch (HRW) reports that approximately 20,000 of these individuals have successfully registered with the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

Ismail fled Myanmar in 2013, and has vivid memories of his homeland. He often sings in his native language about the atrocities faced by his community.

Some 150 Rohingya refugees reside in Faridabad, primarily living in urban slums, making a meagre living by selling garbage or performing hard labour, mostly for low pay.

While the children receive daily lesson - their only hope for an education - their parents sort out garbage in a massive pile of waste just outside their shanties. The towering apartment buildings abutting the camp highlight the stark contrast between the two communities' living conditions.

"I am not able to enroll the students in government schools because we lack the documents. I strongly believe that a community cannot move forward without their language, so I started teaching them on my own," Ismail told FairPlanet.

While Ismail's classes draw around 25 to 30 children from various age groups, they are vulnerable to the whims of nature. When rainfall occurs, Ismail is forced to cancel classes, as the makeshift room's roof is unable to keep out the water, making it impractical to hold lessons.

Due to a lack of resources, Ismail printed several copies of the Rohingya Alphabet for the children. However, in a devastating fire in January this year, Ismail’s shanty was burned to the ground along with the printed copies. He could only save a single copy from which he now teaches the children.

2017 marked a significant milestone for the Rohingya community with the inclusion of their language in the Unicode Standard - a widely used encoding technology that enables written scripts to be transformed into digital characters and numerical representations,

Historically, the Rohingya people relied exclusively on oral communication, as their language lacked a standardised written form. The nuances of the Rohingya language were studied and documented by Mohammad Hanif, an Islamic scholar who had to flee Rakhine, Myanmar because due earlier instances of violence.

Hanif's efforts played a part in ensuring that the Rohingya language could be accurately represented in writing, paving the way for its preservation, recognition and ultimate inclusion in the Unicode Standard.

This made the language more accessible on a variety of digital platforms and communication channels, including WhatsApp.

Ismail downloaded a digital keyboard that supports Rohingya script on his phone, which allows him to type, display and share written content on his smartphone.

"I can send messages in my native language. I know we have far more problems to overcome, but this has given us more representation and legitimisation," Ismail said with a proud smile.

Muhammad Noor, a member of the Rohingya community, the co-founder of the Rohingya Project and the Rohingya Vision (RVISION) - the world's first Rohingya Satellite television channel, played a critical role in the digitisation and standardisation of the First Rohingya Alphabet through the Unicode system.

Noor explains that the Rohingya language has been spoken for centuries, but the script used to represent it has evolved over time. In the early 1980s, a group of scholars gathered in Myanmar to develop the Rohingya script, with Mohammad Hanif being among the leading members of this effort.

"People embraced the language in Myanmar," Noor told FairPlanet. "The government in the 1980s was on alert that there is a movement of Rohingya unification, because language itself is the core engine for the entire culture. The [Myanmar] government started a crackdown on the language and it went underground."

Noor's father approached him with an idea: if the Rohingya script were digitised, people would have greater access to reading and writing in their language. With this goal in mind, Noor reached out to various experts for assistance and conducted extensive research. After seven months, Noor successfully developed the first Rohingya digital font.

Rohingya people subsequently began to write a variety of texts in their language, including several chapters of the Quran. Encouraged by this success, Noor decided to take his efforts a step further by approaching Unicode.

"From 2011 up to 2017, it took us five-six years to get the proposal accepted at Unicode. This legitimised the language. I also approached a couple of organisations like Google to adopt the language," said Noor.

India's approach to refugees, particularly the Rohingya, is characterized by a notable lack of a coherent national policy devoted to addressing their needs. The Indian government refers to the Rohingya people as "illegal foreigners," and does not formally acknowledge them as refugees.

Notably, India is one of the few nations that have not endorsed the 1951 UN Refugee Convention, which lays out guidelines for defending and assisting refugees. This deprives them from accessing basic services such as education, employment and healthcare.

"The Rohingya [in India] are struggling in several ways. One is statelessness, and there are other problems like documentation issues, no access to healthcare, and so on," Noor said. "After the rise of the BJP [Bharatiya Janata Party, India’s ruling party], we saw similar scenes [to the ones] happening in [Myanmar]. Makeshift camps were burnt down, there was an anti-Rohingya campaign carried out in Jammu. Compared to Bangladesh and Malaysia, India has been aggressive towards the Rohingya community."

Bashir Ahmed and Jameela Begum sent their three daughters to attend classes run by Ismail. They want a different future for their children - one in which they do not have to perform menial jobs for meager pay. Before heading to sort out waste, Begum prepares her daughters to attend the makeshift classroom.

"My children deserve a good education," she told FairPlanet. "We also want them to remember their language. Wherever we go, I want them to remember our roots and where we came from. It is absolutely important."

At around 5:00PM, in the sweltering heat of Delhi's NCR region, Ismail dismissed the class and sent the children home.

"Even if I am not able to go back to my country, I am content that I am teaching these children the language of their homeland," Ismail said as he locked the makeshift classroom. "Our identity is our language and our culture. We will always carry it with us."

Image by Asma Hafiz

By copying the embed code below, you agree to adhere to our republishing guidelines.